Magnets magnets everywhere…

A blog post from Quantum Diaries by Anna Phan, published on Tuesday, May 17th, 2011

In my previous posts, I’ve mentioned that LHCb contains a dipole magnet to help measure particle momenta. Particles normally travel in straight lines, but in a magnetic field the paths of charged particles curve, with positive and negative particles moving in opposite directions.

By examining the curvature of the path, it is possible to calculate the momentum of a particle. Particles with greater momentum bend less than those lesser momentum. This is because a particle with greater momentum will spend less time in the magnetic field and thus be affected less.

Note that both the above images are from The Particle Adventure which is a fantastic website to learn the basics of particle physics.

Here is an image of the LHCb dipole magnet with some people for size comparison. The magnet is essentially a very large horseshoe magnet with the upper coil being one polarity (N for example) and the lower coil the opposite (S) where the magnetic field is the strongest between them.

Of the major LHC experiments (ALICE, ATLAS, CMS and LHCb), the only other that uses a dipole magnet to bend charged tracks is ALICE. Actually, ALICE has quite an interesting magnet configuration, which you can see from the following schematic. There is a large solenoid magnet (coloured red which was used in the L3 experiment at LEP) in the central region, and a dipole magnet on the single arm forward muon detector.

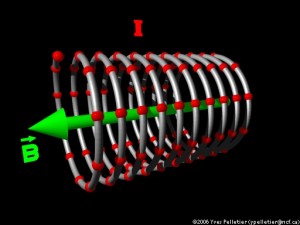

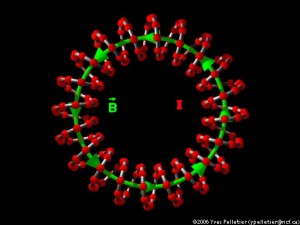

What’s a solenoid magnet? Here is a schematic of one from . This type of coil configuration generates a nearly uniform field inside the windings and a comparably weak and divergent field outside. It is the preferred type of magnet within cylindrically symmetric detectors. In fact both ATLAS and CMS use solenoid magnets. physics animations

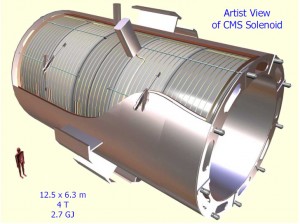

Actually, solenoid is part of the CMS acronym, Compact Muon Solenoid. At 12.9 meters long with an inner radius of 2.95 metres, an outer radius of 3.8 metres, and weighting 12,000 tonnes, the experiment contains the world’s largest superconducting solenoid magnet.

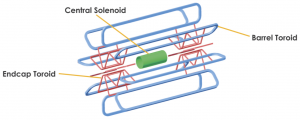

ATLAS on the other hand is named after its other magnet system, A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS. One of the key design features of the ATLAS detector is the unique hybrid superconducting magnet system. It is an arrangement of a central solenoid surrounded by a system of three large air-core toroids, measuring 26 m in length and 20 m in diameter.

What’s a toroidal magnet field? Again, thanks to physics animations, here is a schematic. As you can see, coils are oriented so that the magnetic field goes around in a doughnut type shape. (Toroidal is just a fancy mathematical description for a doughnut shaped object.)

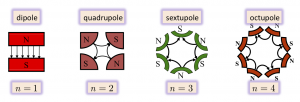

Of course, the LHC experiments aren’t the only uses of magnets at the LHC. The accelerator system is full of them. Dipole magnets are used to steer the protons around the ring, quadrupole magnets are used to focus the beam, sextupole magnets are used to correct chromaticity, octupole magnets are used to correct field errors. What are all these magnets? Here is a nice diagram from some lecture slides I found. As you can see, they are named after the number of magnetic poles they contain (2, 4, 6 and 8, the n in the diagram counts the number of pole pairs). The arrows on the diagram shows the direction of the magnetic fields that each of the magnets produces.

In terms of beam acceleration, dipoles and quadruples are the most important. In fact, if you look carefully at the Fermilab logo below, you might notice the superposition of a quadrupole and a dipole magnet…

I could continue, but this post is getting very long. I hope this very brief introduction illustrates how important magnets are in experimental particle physics. Personally, I wish I had known this when I was taking electromagnetism and electrodynamics in my undergraduate studies, which were actually my worse physics subjects in terms of marks. I really should have paid more attention!

< PREV | NEXT >